How was it possible for us to process the raw materials for our multiversity on Venus of all places?! Acid rain. Temperatures as hot as an oven cleaning cycle. A series of volcanic eruptions had caused a runaway greenhouse effect. The resulting density of the CO2 rich atmosphere as great as that at 3000 feet under sea level. A slow rotation.

This environment had crushed the Russian probe, Venera 7, when it made the first Venusian soft landing on December 15, 1970.

Venus, it has been theorized, lacks water on the surface, plate tectonics, and abundant life enough to correct the extremities of that environment and make it habitable. But in 2020, observers of Venus captured evidence of phosphine gas in the planet’s atmosphere that suggested the presence of life.

A race to Venus began. We hoped we would be gone by the time this race was won—if Earthling societies were still able to sustain such ambition against the decay of their infrastructure.

How did SIA solve the Venus problem?

The Venus solution lays in that first probe in 1970, the lucky Venera, Russian for Venus, morning star. Also for Lucifer, the fallen angel. The intersections here of the goddess of love and the angel who refused to worship man are perfectly suited to the explanation we must offer.

On one side of the story, three astronomers in the Soviet Union met in graduate school and began to scan the skies and to document the existence of astral bodies, lesser planets or asteroids caught in the gravity of the solar system. Lyudmila Chernykh, born 1935 – died 2017. Nikolai Chernykh 1931 – 2004. And Tamara Smirnova 1935 – 2001.

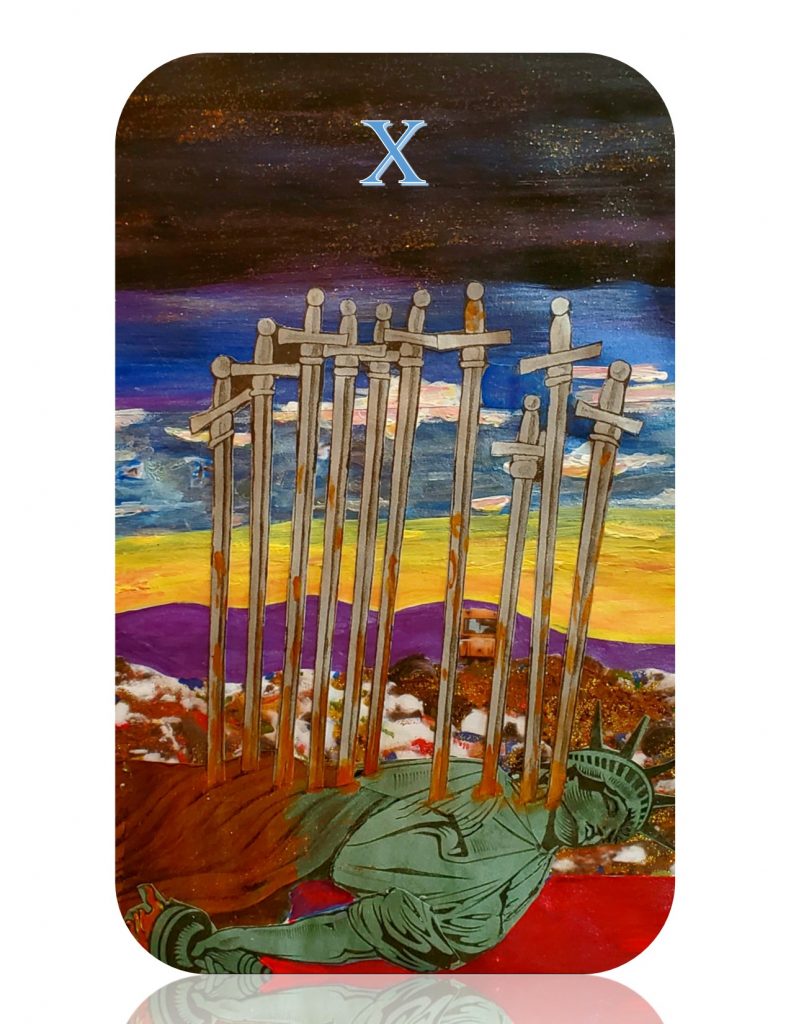

In tarot, threes present us with expectation, with collaboration, with betrayal, and with reconciliation. In these passionate connections, the problem of torn loyalties presents itself, the challenge of third parties that take from two: of lovers, work, and children. Here is the place where two produce a third and the world is never the same. Defection, hybridity, all are in play as a third comes in.

Lyudmila was the kind of woman you did not expect to find behind a telescope. Tall, femme, brash and brilliant, she possessed the hearts and bodies of both Nikolai and Tamara. But 1958 was a dangerous time for the thing she had with Tamara. So, she married Nikolai.

It was understood by Niki that Lyudmila’s love for Tamara did not leave when he placed the ring on her hand. Tamara, calm, deep, with her dark humor and her charisma, her sleek, auburn head bent over her calculations, her steady shocking eyes when she looked up to meet Lyudmila’s. Tamara’s was the gaze that still tumbled Lyudmila into the void where fire, water, and the very matter between the stars ruled her.

When Lyudmila chose Niki, Tamara went silent, cut through with her loss. But all three were assigned to the same project for the next 7 years and she found a way to work companionably with her married friends. They mapped the stars. Then Nikolai was drafted into the Venera project. Lyudmila left with him. Tamara went onward alone.

Across the Pacific, a daughter was born to Gloria Bitterwater, a west-Canadian Indigenous medicine woman of the Eagle-Wolf moiety. When she turned 18, Bernice asked her mother again who her father was and her mother told her this time of a geologist, John Ralph, who had come to study volcanoes in the region. She had gone with him as guide and to protect the sacred places he wanted to study. Gloria did not tell Bernice what happened. She said, “and then, you came along!”

It was John Ralph, still studying volcanoes who took Bernice to Siberia. This was where she, 19, met Tamara, then 33, high on an icy mountain where the telescope pointed to the stars, below which rested an ancient, sleeping volcano, which her birth father wanted to study.

Before Bernice Bitterwater left for the airport and Siberia, Gloria had taken up her hand, which was brown and small and sure, just like her mother’s. The medicine woman put a pouch into Bernice’s palm and said, when you go there, look for the red bird, it is what is missing. And she called the pouch a word in Athabascan, one that Bernice, who spoke her native tongue (as well as English, Russian, French, and Greek), understood well.

Long ago, her people had come across the ocean on boats. They had brought this red bird, a kind of mushroom. The ancient people had made it a part of their medicine. It had flourished deep in their mountains. But then, inexplicably, it had left. The ancient people tried but could no longer cross over to the land where it came from.

Bernice was to bring the red bird home with her from Siberia. She was to leave the pouch in Siberia in return.

But something else happened too.

Bernice met Tamara. And like Lyudmila before her, the sight of Tamara’s dark head bent over her calculations, the raising of her gaze. From the very first moment Bernice met her, it was as though she was shot through with stars and joy.

Bernice found the red bird deep in that Siberian volcano. It was unmistakable. She brought it home to Gloria Bitterwater and her people. When she left Siberia and Tamara, she followed her mother’s direction, to leave the pouch there. But she left the pouch with Tamara, including the small start of the red bird she had added.

She said simply, “here.”

She trusted her heart to show her that Tamara was the part of Siberia she was meant to give the medicine to. She could always feel Tamara’s wound. She felt it against her own ribcage, where she too had been struck with love. She intuitively understood how she reminded Tamara of Lyudmila—for Bernice was also brash and brilliant and femme, in her way. In a way that shocked Tamara with memory and sent her spiraling into ancestral losses as well.

“What is this?” said Tamara. And Bernice answered with the Athabascan word.

When Tamara looked into her eyes with a question, Bernice with her command of many languages struggled, wanting to meet that sweetness, that mutualness, that fire. “It is not easy to translate” she said. “I guess it means world. It means home. It means light.”

Then Bernice went home.

Tamara put the pouch under her pillow, missing her lover’s body. Then, she began to dream.

Now, Tamara was a scientist. But love makes even a scientist open in ways that bear no explanation. She had been touched and changed by love twice in her life, already, by the young age of 33.

Let’s say, it took time. Let’s imagine the persistence of the dream, how repetitive, how she woke grasping for what she had learned she must do. Grabbing at pen and paper to jot the dream down before it slipped away, unaided as dreams are by the remembering parts of her brain, which had been resting while she slept, instead of grooving.

But one day, before it was too late, she took the pouch to her old love Lyudmila and she said, this must go to the Morning Star on the Lucifer 7. Does that make sense?

And it did make a little bit of sense to Lyudmila, who had become a mother in the last few years. She looked into Tamara’s eyes and she felt the same old falling feeling. Lyudmila was never the kind to harden or to put on armor. She was not one to remember or dread pain. She knew it had taken Tamara courage to come back. She accepted without questioning the love gift of the pouch.

Nikolai was like Lyudmila in this way—he could never say no to the one he loved. And in 1970, as he prepared the probe for the journey to Venus, he slipped the little pouch into a nook. He knew how fine the calculations for a soft landing could be. He would always wonder whether that pouch had made the Venera 7 the lucky one to land.

Lucky before it caved under the pressure of the atmosphere, that is! He smiled and he stroked his beard when he thought of this.

In the darkness of the Venera 7, the red bird birthed a small colony, integrating with the other medicine in the pouch, lighting the probe as it coursed through the void, feeling the dark matter, the map of the stars.

Little world, home, light. The Mycelium burst forth onto Venus from the probe as it landed.

She flipped the antennae helplessly into the hot mud, but not before she had sent out a message back to Nikolai and the Russian astronomers:

“Hot, hot, dry, no water here, heavy.” said the Mycelium, giving herself some forty years to prepare the way for us.