When all of this started, there was a genre of science fiction concerned with the practicalities of space travel: a man stranded on Mars grew potatoes; when the water filtration on the ship broke down, the travelers captured crystallized water released from the ship’s membrane; CO2 levels made astronauts go mad and projects ended in pragmatic tragedy.

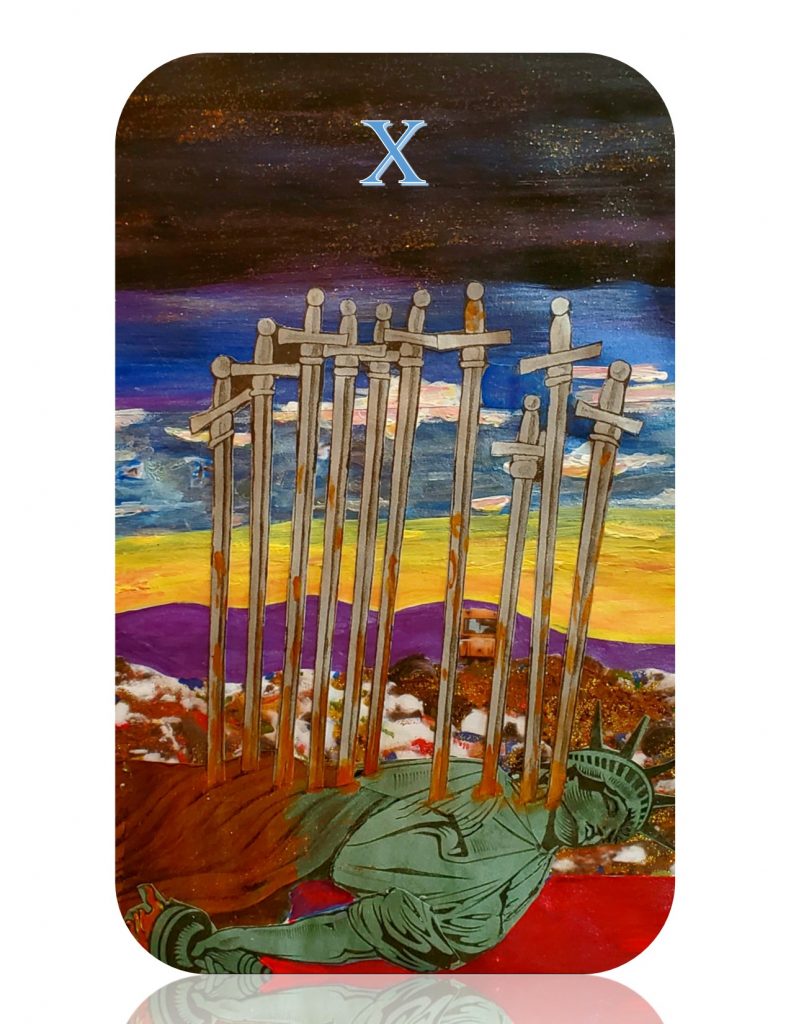

The first SIA mission to space began at this level, in a recycled clunker of a ship bound for Venus. They were brave in their suits with their oxygen tanks and their detailed plans for how to cycle down the energy needed for the very basic earthly mechanism of photosynthesis that close to the sun.

But they also had an ally with a capacity for great leaps of intelligence. Part of their experiment was that symbiotic relationship. Even as they flew towards Venus, the Mycelium and the human workers processing the waste collected by the golden women grew their technology in leaps and bounds, so that they soon had a vast empire of waste management and recycling. Then. building and growing, they came to a way of surviving and of concealing the magnitude of their project beneath the soupy atmosphere of that golden planet named, ironically, after the goddess of love—for she rained down acid.

Mycelium that had developed a tolerance to sulphuric acid in the fermentation industry’s waste management processes in China expanded its ability to resist, but also transform the fatal rains that fell constantly from the Venusian skies. The cleansed rains, the clouds of carbon dioxide, breathed and filtered and transformed into bright pools of sulfur, fed the gardens that soon grew into alien rainforests that exhaled oxygen.

The SIA and their ships could have remained there. But the cloud thickening mechanisms they built to mute the heat of the sun for their gardens numbed and dulled the light and could not meet their need for blue skies, for golden warmth on their skins and lashes, and for enough starshine to bake their clothes and the crowns of their heads on a hot summer’s day.

There was a Ray Bradbury story about this longing. The sun broke the clouds for one hour every seven years.

Besides, they would need to stay away from Earth for over a millennium. Were they so close to the blue swirls of their home planet, close enough to view the land of their ancestors as a star in the sky, they might not be able to resist that call.

They knew Earth needed time to purge and then to heal. They were determined to give it to her.

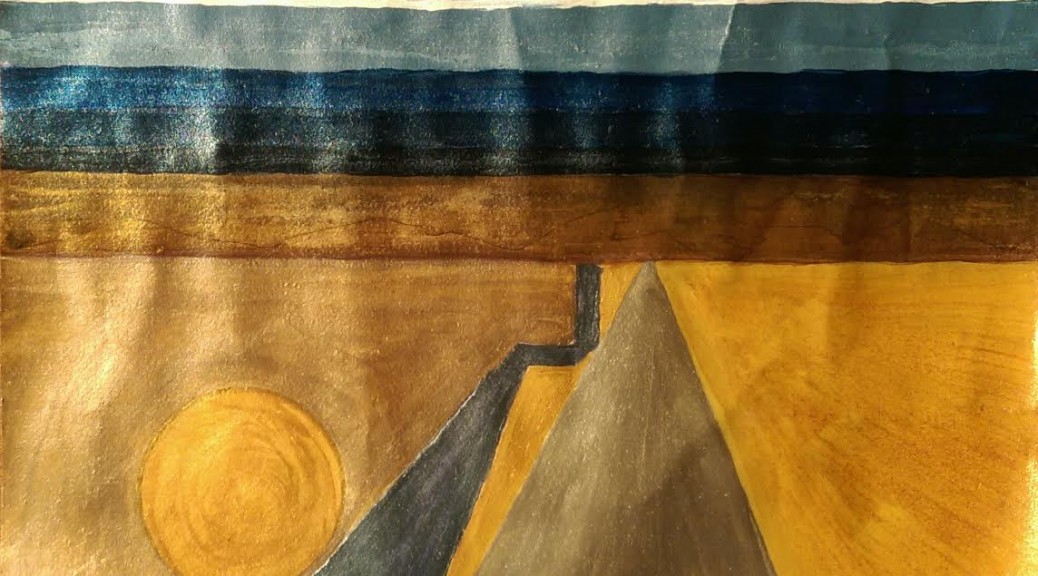

The astronomers of SIA had identified a pattern in the great randomness of the Milky Way in maps modeled after histories marked in ancient sites, at Stonehenge, at Machu Picchu, at the Great Pyramids under the gaze of the Sphinx, according to the Mayan calendar, and in alignment with those other mysterious tools for marking time and mapping space that were monuments to the old ones.

In 2050, the pattern would align again.

The people of SIA and their Multiversity of Arks would be waiting there.

At the Mirror, ready for the opening of the gate.