Juno lay in her beloved body, naked on the subtle rise and fall of the Aegean. Her hair spread out over the surface, pulling gently at her scalp. She could hear the sands and stones moving on the sea floor. Her slim feet dangled in the dark water. That liquid resistance stroked her arches.

She wiggled her toes and felt the new presence there. The Wiki. Between her big toe and her first toe on her right foot.

Juno had returned to Crete in the early morning hours, stepped off the slow ferry into Iraklion and driven her rented Fiat down to Kalantos under the starry moonless sky. She thought of a theory about the space between the stars, of dark matter that prevented galaxies from flying apart.

She felt how she did not fly apart. She felt the network now interlacing itself into her vagus nerve, mirroring and tying into her body. Already the bottoms of her feet and the palms of her hands were tattooed with delicate patterns, like maps of neurons or of the web she had seen and could call up quickly now into her mind’s eye.

Driving here, she had felt the road and her car handling tightly, hugging curves and opening wide on the empty highway. She felt when the other cars had turned away into the city for the night. She drove up into the mountains. The last cars had split off, like hairs standing up on the back of her neck, bound for country lanes amidst orchards she sensed growing in the darkness. Olive and orange tree roots met capillaries that spread through Earth. They let the eucalyptus at Kalantos know she was coming.

Earth intelligence flooded her. She laughed. The Wiki did that, made you a little high. It was a side effect encouraged to counteract the negative effects of the fungi her body was integrating.

It would take time to process the massive download of information, or so the SIA scientists imagined. She was an experiment.

Just another transition in a long history of them, Juno thought.

The ferry had been a challenge. With the Wiki, people shone around her. She could see their stunted and amputated ganglia, as well as their reaching and flinching auras. She had let herself weave amongst them, hot gold amidst their reds and greens and blues. This was priestess work.She could sooth, feeding their unmet desires to connect, until all slept, cocktails and bags of crisps forgotten.

While they slept, her consciousness sought those who were awake.

Seeing out through navigational instruments and the captain’s brown eyes, behind her knowledgeable squint and steady hands, Juno helped steer the great ship from island to island, waking the passengers in time to depart through the belly of the ferry. They rolled their bags into the ports, going on their sleepy ways.

When she disembarked, she had taken her keys from the efficient rental car dealer at the port, assuring him that yes, yes, she could drive stick. Why the United States had gone automatic, they agreed to wonder, shaking their heads. She felt his laugh push his sternum out into the space between them. Then storing her bag, Juno started the little car up. She tuned into the map of her mind. No need for her cell phone now.

Before the Wiki, she had made conscious decisions. With it, she operated through a now perfectly timed physical impulse. Her body drove the car and looked out to the night, sensing without needing to know that a car was approaching, then peeling off. Her toes knew to tap the brakes, to pause for a wildcat who would be walking across the road here. The kri kri, wild goat, would swerve at the sound of her engine and wind her way back up amongst the shrubs to seek her pre-dawn snack.

Juno’s foot pressed pedal to the floor and the wind whirled into her skin.

She was part satellite, part plant intelligence, retracing the routes of roads like filaments unto the sea as the early morning darkness swelled with promise. A bumpy dirt road roared up at her with anticipation, until she parked. Barefoot, she had walked the short distance over the coarse, cool sand, stripped off her travel heavy clothes, and slipped into summer warm waves.

Water worked as a buffer, not silencing but muting the connections. That is why she had come here to Kalantos to rest, just a few feet out from the easy surf.

She was surprised when she heard her name called out over the water.

“Juno!” It was Xan.

“Juno!” It was Attie. Juno found her feet in the sands, felt the planet speak to her again, gently, just hushing her startled heart.

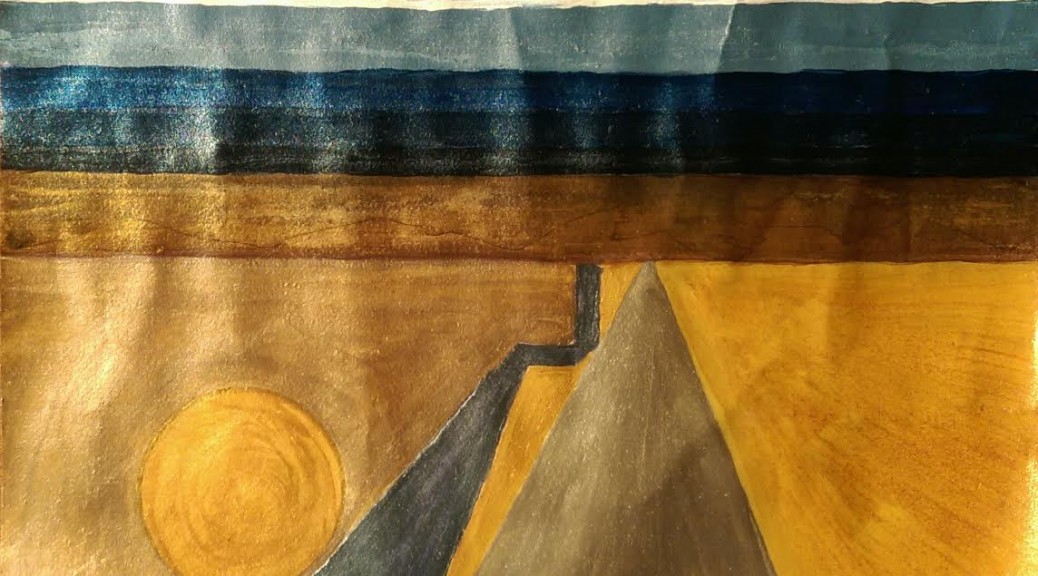

For the first time she could see these two women: the amber of Alexandra reading the mind of the galaxy, her faint and holographic memory of what was, of what would be, the licking of a snake’s tongue, of Earth’s vague, terrifying future.

Atalanta’s indigo aura went deep down into the roots and out into nerves and hearts – of birds just waking into the new day. A cat laying casually at the edge of shrubs above the beach, lifted her eyes with Attie and looked at me too.

I saw how Juno knew for the first time.

“Priestess, welcome home,” we said.

And we did not need to, but we reached out for one another’s hands, the cooled and solemn palms and fingers, the warmth of our blood, the meeting of green and brown and blue eyes.

There is still nothing like hugging a dear friend, Juno thought, feeling more. She was now woven into the muscle and bone and minds of these women…with whom she was ready to travel to the stars.

Funny, she thought, how the teacher can feel like the student.

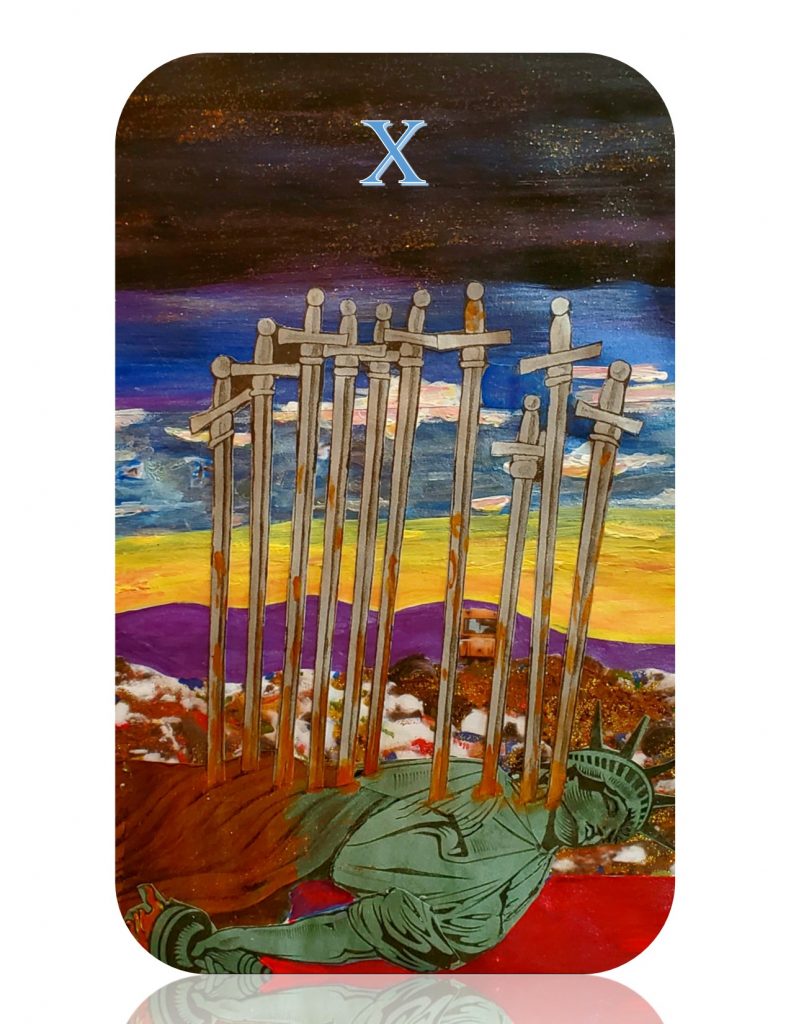

And in this moment, we all remembered, how arbitrary the structures on which we can arrange our relations.